Geography needs to face up to colonialism. The omission of race in the KS3 national curriculum and GCSE content leaves geography vulnerable to reproducing colonial hierarchies and supporting monoculturalism which erases the lived experiences of so many of our students. The erasure of race in studies of the Development Gap at GCSE allows systems of domination to remain uninterrogated and appear natural. Responding to the shocking silence from geography education following the Black Lives Matter movement, Steve Puttick and Amber Murray state bluntly, ‘Geography Education in England has a problem with race’. They note that the word ‘race’ does not appear once in the KS3 national curriculum or in the GCSE.

In Summer 2020, in the middle of the Black Lives Matter protests, I had a memorable lesson with a group of students. They taught me about what an anti-racist curriculum looks like. These were their key ideas:

- Humanity – one student said, tearing up: “How can I watch a person get shot and not feel anything? How can I be so desensitised?” We need an education system that makes us feel connected to other humans and expands our empathy, rather than seeing people as numbers.

- Empower – students said that wanted to learn narratives of Black leadership which they can feel proud of. We need an education system that gives students the historical and cultural knowledge which can help them feel grounded in their lives and communities.

- Voice – students said that they feel like race is not recognised as an issue. They felt resentment towards other minority groups and issues that were given a voice in the school. We need to create spaces to talk about race.

- Question – we need to ask difficult questions and challenge stereotypes. One student asked, “why black violence is gang violence, brown violence is terrorism, and white violence is less talked about in the news”. Students can teach us with their questions.

Geography has an important part to play in the decolonising process. It is a discipline which emerged as the science of European imperialism. The geography of exploration, colonial geography, and tropical geography were driven by a desire to map, conquer and influence colonised territories. When European colonists “discovered” lands and populations, they named it as a territory and mapped it as part of a process of domination and appropriation. Geography has always played a key role in the relationship between knowledge and power. Despite efforts to decolonise the discipline geography continues to be an important tool for domination, by promoting visions of ‘objectivity’, prioritising economic development over all other forms of knowledge, exploiting landscapes, and even manipulating populations.

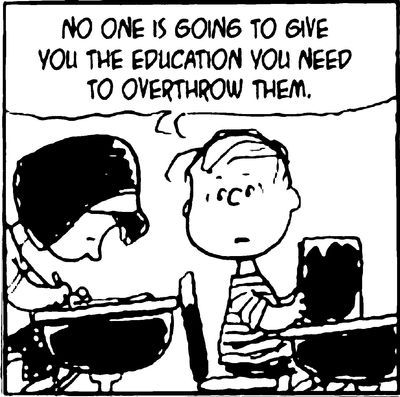

Yet there is hope – Geography is also key to liberation. Geography teachers and educators today are tasked with decolonising the curriculum. This means to ‘make visible, open up, and advance radically distinct perspectives and positionalities that displace Western rationality as the only framework and possibility of existence, analysis and thought’ (University of Bristol Decolonising Education Course). Decoloniality is an evolving process that questions knowledge and opens new ways of thinking. It is of course anti-colonial but it also seeks to highlight the pluriverse of systems of knowledge and thought and think beyond the colonial framework. What this means is an effort to engage in ‘thinking otherwise’ outside of the categories, hierarchies and binaries of coloniality in an effort to think relationally.

Geography Education needs to step up to the challenge of decolonising curriculum. We can use our students’ enquiry to inspire this process and look to scholars in Black Geography, Indigenous Geography and Decolonial Geography to guide us. It is the subject of ‘powerful knowledge’ and together we can create an inclusive curriculum which will be part of creating a more just and sustainable world.