London’s everyday urban morphology has been deeply shaped by legacies of empire. Trafalgar Square, in the centre of London, was commissioned as a celebration of British naval power in the service of its imperial ambitions. The repurposing of the building on the western side of the square as the Canadian High Commission in the 1920s, and the addition of South Africa House on the eastern side of the square a decade later, offer powerful symbols of the political and economic links between Britain and settler colonial states in the 20th century. However, almost since its creation, Trafalgar Square has also frequently been the site for political demonstrations against the policies and interests of the British state.

One of the most visually startling comparisons of these two histories of the Square occurred in the late 1980s when, for just short of four-years, the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group (commonly known as City Group or City AA by its members, and CLAAG by the police and its detractors) maintained a continuous Non-Stop Picket outside the South African Embassy. Their constant presence there was a major irritation to the defenders of apartheid in Britain, and there could not be a starker comparison between the colourful, weather-worn, banner that marked the site of the Non-Stop Picket, and the imposing white edifice of South Africa House. In this article, I want to tell the story of the Non-Stop Picket, but also to draw out some lessons from it that might be valuable for those of us interested in ‘decolonizing’ Geography.

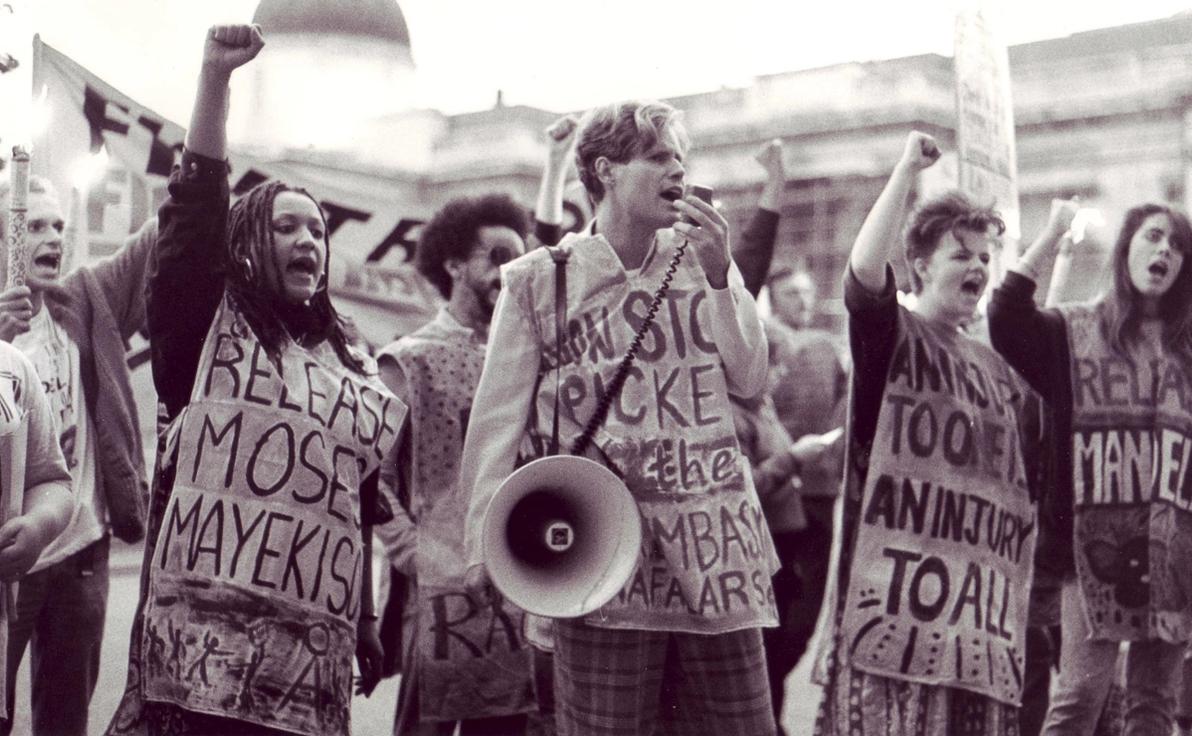

Figure 1: Photo from the Non-Stop Picket in June 1986, taken by Jon Kempster and used here with permission.

The Non-Stop Picket began on the 19 April 1986 and continued until 13 days after Nelson Mandela’s release from jail in February 1990. The idea for a non-stop protest outside the South African Embassy had been the idea of the exiled South African campaigner, Norma Kitson (her husband, David, had been one of the longest-serving white political prisoners in South Africa). Inspired by the growing mass movement against apartheid in South Africa in the mid-1980s, Kitson was committed to building maximum solidarity on the streets of Britain with the South African anti-apartheid opposition. However, it is probably fair to say that, when she proposed a Non-Stop Picket until Mandela was released, she never anticipated that the group would be committing itself to a four-year long protest. Nevertheless, her idea inspired hundreds of (mostly young) Londoners to both make and maintain that commitment.

Alongside Norma Kitson, the Group’s main leader was Carol Brickley, a graphic designer who had grown up in the Staffordshire coalfields and became politicised while at art college in the early 1970s. Having two women leading the group shaped its political culture and encouraged younger women to play an active role. Charine was a young Black woman with family links in Sierra Leone, who had first become involved with City Group, as a teenager, shortly after its formation in 1982. Sharon and Georgina grew up in the south-east London suburbs and joined the Non-Stop Picket by chance on the day it was launched. That summer, they left school and found work as secretaries in the West End, so they were closer to the Picket. Deirdre was one of several young Irish migrant workers who found that the Picket rooted them in London. For Ruby, a young South Asian woman, time on the Picket forced her to confront the institutional racism of the Metropolitan Police for the first time.

By positioning itself in front of the South African embassy, the Non-Stop Picket sought to cause greatest embarrassment to the representatives of the apartheid regime in Britain. This gave a focus to the group’s protests, but the longevity of the Non-Stop Picket benefitted from its location in other ways too. Because South Africa House was in such a prominent and accessible central location, it made the Non-Stop Picket far more visible than it would have been if the embassy was tucked away in a quiet street in Belgravia or Mayfair. People commuting to work, going for a night out in the West End (or waiting for a night bus home afterwards), and tourists visiting the National Gallery passed the Picket at all times of the day and night. At the heart of a metropolis striving to present itself as post-imperial, the Non-Stop Picket made an intervention into the everyday urban geography of London and forced global questions of racialisation and the ongoing legacies of empire onto the streets of the city.

The pavement outside the embassy was, at the time, one of the widest in London, and this enabled the picketers to stop passers-by, engage them in conversation, and encourage them to get involved. While few signed up on the spot, repeated interactions with picketers enticed many to pledge their time to the Non-Stop Picket. In a time before mobile phones were common, and before social media, the Non-Stop Picket relied on analogue forms of organising. In practice, the day and week was divided into three- and six-hour shifts, and supporters were encouraged to pledge their time to a regular shift. Any gaps in the rota were then filled from the floor of the group’s weekly open meetings which, at the Picket’s height, could regularly attract a hundred or more people each Friday evening. Some shifts survived with only two or three picketers, but at the weekend the Picket would swell to 30, 50 or more people. Saturday afternoons attracted the participation of large numbers of school students from across London and beyond (so much so that some older picketers nicknamed it ‘the creche’).

Time spent on the Non-Stop Picket was time (mostly) spent engaged in political work. Picketers petitioned and leafleted passers-by, they made speeches about the history of apartheid and opposition to it, they engaged in political discussions with each other, and they sang songs in Zulu and Xhosa from the liberation struggle. In these ways, the Non-Stop Picket brought aspects of Black South African (political) culture to the streets of London – through its languages and performance styles. But this also found expression in Norma Kitson’s insistence that women, young people and, even, children should be central to the Picket (in South Africa, in the 1950s, a key aspect of Norma’s political work was teaching Black women skills that the racially segregated education system denied them, so that they could play a more active and expansive role in the struggle). This centring of African political cultures and practices, as much as the group’s commitment to opposing apartheid, helped question and challenge everyday geographies of race and identity in London. The group’s weekly meetings were also a site of political education, and regularly hosted speakers from South Africa who were able to provide briefings and analysis of the anti-apartheid struggle. Through these activities, as well as the practical organising undertaken by volunteers in the group’s office, picketers acquired new skills, knowledge, and confidence.

Figure 2: A crowd gathers for a rally on the Non-Stop Picket in April 1989. Photo taken by Gavin Brown and used here with permission.

Locating the Non-Stop Picket outside the South African embassy was more than a symbolic act. A key demand of the Picket was the closure of the South African embassy until apartheid was over, and the group used its presence (and particularly the singing, chanting and songs amplified through their megaphones) to actively disrupt ‘business as usual’ for apartheid’s diplomats. City Group did not just seek to offer moral support to those resisting apartheid in South Africa. They took direct action (on and off the Non-Stop Picket) to draw attention to the political, economic, and sporting links between Britain and South Africa, and sought to disrupt them, hoping that the end of apartheid would help to reforge those links on decolonized terms. While many picketers initially joined the Non-Stop Picket motivated by a humanitarian impulse to end the violence of apartheid, most quickly learned more about the history and consequences of British colonialism and imperialism. The group linked apartheid in South Africa to these wider histories and argued that those sections of the British ruling class who extracted profit from the racialised division of labour in South Africa’s mines and economy in general, also benefitted from systemic racism in Britain. If the British ruling class benefitted and profited from apartheid, then the interests of those who were exploited and oppressed by them, in Britain, South Africa and elsewhere, were also linked. As one longstanding picketer had a habit of saying in his speeches on the Non-Stop Picket, “every bullet fired from the barrel of a South African revolutionary’s AK47 ricochets through the crystal chandeliers of the Palace of Westminster”.

In the interviews that we conducted with former picketers for our book, Helen Yaffe and I repeatedly heard people describe how they joined the Picket at a point when they felt isolated, directionless, or as if they didn’t ‘fit in’. Many young homeless people living on the streets of central London passed time on the Non-Stop Picket, knowing that they would be treated with dignity there, welcoming the company and safety it afforded them. The Picket also provided a supportive space for lesbian, gay and trans youth (and many others questioned or experimented with their sexuality during their involvement with the protest). The political culture cultivated through the Non-Stop Picket created space in which a range of British social norms were contested – not just those around race. The close friendships and comradeship that developed between pickets, as they spent hours together week after week, helped many to overcome loneliness and isolation. An everyday space of global solidarity also functioned, therefore, as an everyday site of local care and community-formation. For many people, the Non-Stop Picket provided them with an opportunity to get to know people from very different backgrounds to their own; and it was there that many of the young picketers made friends with adults, as equals, for the first time. The skills acquired through running the Picket and organising its campaigns were carried forward into other campaigns and have shaped people’s working and personal lives since. And the political education that people received on the Picket challenged them to think differently about Britain’s place in the world and their relationship to it, spurring many to stay committed to anti-racist and anti-imperialist movements. In these ways, we can think of the Non-Stop Picket as more than a political protest against racial capitalism and settler colonialism in South Africa, it was also a street-based space of informal, anti-racist, political education and collective skill-sharing.

Although the Non-Stop Picket had the release of Mandela as its central demand, the group never restricted their solidarity to Mandela’s African National Congress. City Group was committed to providing ‘non-sectarian’ solidarity to all those political tendencies who opposed apartheid in South Africa. In practice, this meant that the Non-Stop Picket created space on the streets of London to amplify the voices of those South Africans from Pan-Africanist and Black Consciousness traditions who didn’t limit their demands to achieving democratic rights for all South Africans, but who wanted to undo settler colonial structures and relationships in their country and build a decolonized Azania in its place. For teachers who are committed to decolonizing Geography, the Non-Stop Picket provides a useful case study in how to build a grassroots movement in Britain that is in solidarity with decolonial movements elsewhere. An archive of City Group’s papers is now publicly available at the Bishopsgate Institute, offering a wealth of resources for thinking through these issues. Studying the decolonial analysis and praxis of the Southern African movements who opposed apartheid helps challenge Eurocentric assumptions about who produces geopolitical theory and knowledge. But I also think it is a powerful reminder (to quote Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang) that decolonization is not a metaphor.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Gavin Brown is Visiting Professor of Geography at both the University of Sheffield and University College Dublin. He is co-author, with Helen Yaffe, of Youth Activism and Solidarity: The Non-Stop Picket Against Apartheid. His website with further information about the Non-Stop Picket can be found here, and a video of the spectacular launch of his co-authored book can be seen here.

This article is the first in a mini-series looking at the theme of 'everyday geographies' through decolonial and anti-racist lenses. It is also published in solidarity with striking members of UCU.

The photo at the head of this piece was taken on the Non-Stop Picket by Jon Kempster, and is used here with his kind and generous permission.