Racism is endemic in schooling. Deep-rooted and institutionalised, it impacts upon the everyday experiences of students: it saturates all, from curricula, to teachers and teaching, to school policies. Rarely is it given the attention it deserves.

In 2020 I interviewed secondary school teachers in Greater Manchester, and published the subsequent report, Race and Racism in English Secondary Schools, with the Runnymede Trust. Following a long body of critical scholarship that precedes it, the report draws attention to some of the key issues in education.

‘The teaching workforce is still overwhelmingly white’, it notes. As Bernard Coard noted over 50 years ago, this has very real implications. Last year, Hillman found that in England’s state schools, ‘Black and Asian pupils are three times less likely to have teachers who look like them’. Whilst there is one white teacher for every thirteen white students, there is one Asian teacher for every forty-three Asian students, and one Black teacher for every forty-two Black students. In some regions the figures are much starker. They are starker too, in the more senior roles (such as headteachers). Whilst diversifying the teaching force is important for all students, not least because of the message that representation transmits every day, it is much more important that schools ensure all teachers are racially literate, and committed to antiracism. Nadena Doharty’s work demonstrates the harms caused by teaching that lacks racial literacy. To radically transform schools, racial literacy has to be a prerequisite for entering the profession, and a repeated and ever-present commitment throughout a teacher’s career.

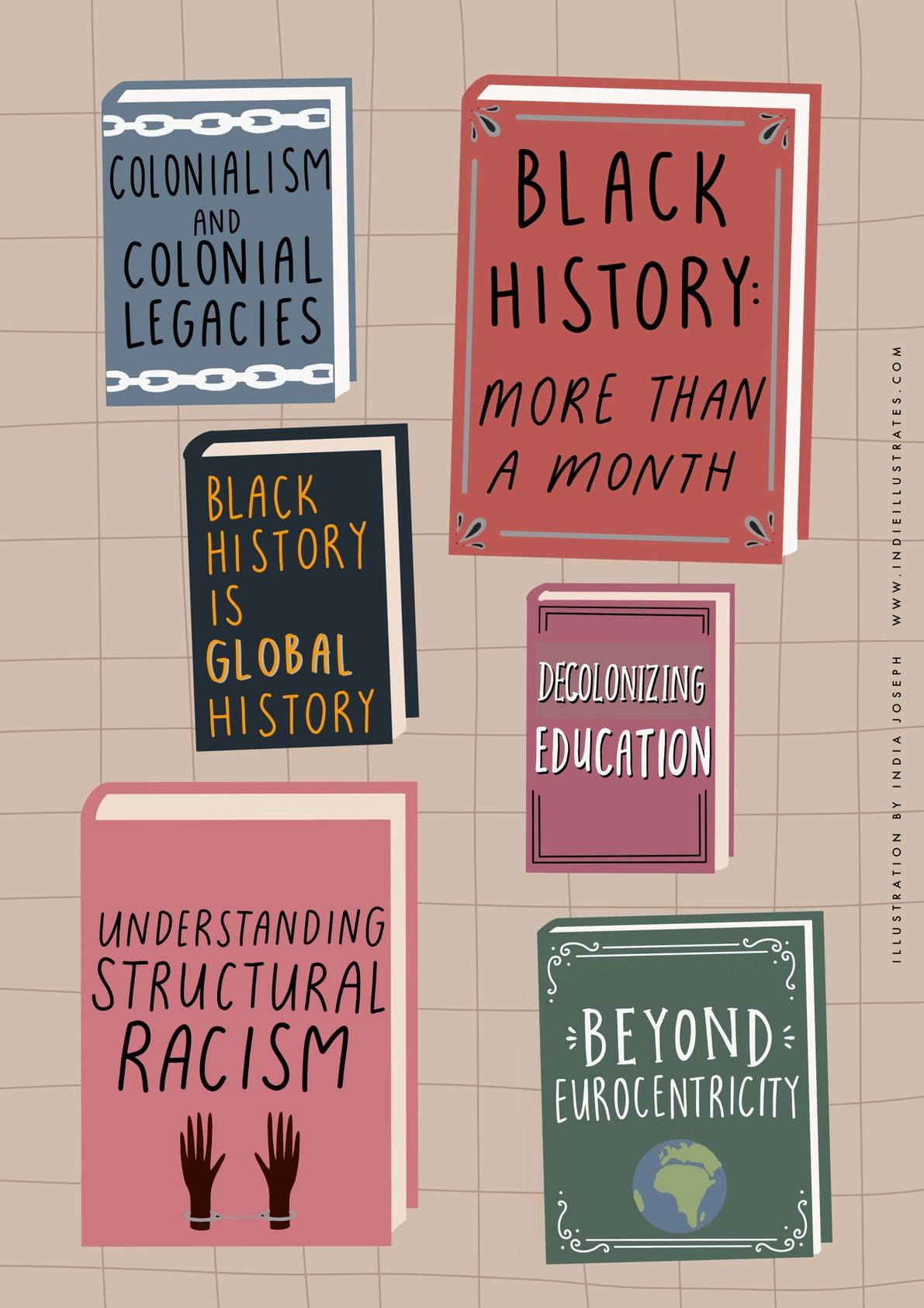

If teachers are to teach in ways that promote and embody antiracism, then this needs to be enabled by curricula. This was another key issue highlighted in the report, and illustrates the importance of the work that groups like The Decolonising Geography Educators Group are engaged in. Curricula too often fail to reflect the diversity of contemporary society, and rarely engage with the colonial legacies – or racist underpinnings – of contemporary Britain. As one teacher explained,

"… the curriculum itself is very narrow, history – it’s all about white history, it’s about kings and queens. What is all that about? You are not talking about colonialism, you are not talking about the East India Company, you are not talking about slavery, you are not acknowledging any of that stuff – it’s all about kings and queens, about Henry 8th was promiscuous and he married all these women."

The erasures and distortions produced and perpetuated by curricula are important because they play a role in shaping student views on the social world (though many students find more critical education elsewhere, in supplementary schools, for example). These distortions deny the ways that structural forces (white supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy) shape our deeply unequal social worlds. Like teaching, curricula do not stand in isolation. Rather, meaningful transformation would need to be supported by changes to textbooks and resources, and on exam boards whose requirements play a key role in dictating what is taught.

In the report, I also call for an overhaul of school policies to embed a culture of antiracism in schools. One important point here, that I did not initially articulate in the report, is the need to find ways to combat racism without relying on harmful ‘zero-tolerance’ policies that rely on school exclusions. Since the publication of the report, concern over school policies has only increased in prominence, particularly with regard to school uniform policies that discriminate against Afro-textured hair, and Black students. Despite the growing protest and resistance of students, parents, academics, and activists – which has included two legal cases – students continue to be subject to disciplinary procedures because of their natural hair. This social control of Black student’s bodies is a stark illustration of the way that institutional racism operates at the level of the everyday. However, in the Pimlico Academy protests, the Halo Code collective’s work in producing a charter for schools, and the ongoing campaigning of many others, there is no shortage of hope.

The impressive work of campaigners against the Islamophobic PREVENT duty is also worthy of support from those of us committed to improving the everyday educational experiences of minoritised students. So too, is the vital work of No More Exclusions who, highlighting the devastating (and racially uneven) impact of school exclusions, have called for a moratorium on school exclusions. Their recent report, ‘What About the Other 29?’, should offer food for thought for all of us.

Another issue highlighted in the report, that has increased in prominence since the publication, is the presence of police in schools. In the report, I showed that ‘teachers have legitimate and urgent concerns that should be heeded’, noting that the negative impact is felt most acutely by racially minoritised, and other minoritised students. More substantive work on this issue has since been produced elsewhere, such as the Decriminalise the Classroom report, co-authored by Laura Connelly, Roxy Legane, and myself. The recent horrifying case of Child Q, described by Professor Gus John as ‘state-sanctioned rape of a minor’, illustrates the profound harm that a police presence in schools can have on students, in this case a Black girl. As evidence of harm mounts, and school boards in the US act to remove police from schools, it would be a mistake to see the Child Q case as an aberration: it is, instead, the tip of the iceberg. As Jas Nijjar has argued, police-school partnerships are part of the ‘war on Black youth’.A petition launched following the Child Q report has already gained over 35,000 signatures, and resistance is growing. If we are cognisant of the deep-seated institutional racism in British policing (we certainly should be), those of us concerned about racism and injustice in schools have to recognise the presence of police in schools as intolerable. As respondents to our Decriminalise the Classroom report made clear, those funds would be far better invested elsewhere – in counselling and mental health provision, for example. Those concerned about this issue should check out the No Police in Schools campaign website.

The harms perpetuated by our education system are profound, wide-ranging, and extend way beyond those pointed out here, or in my original report. As the Black Lives Matter movement has brought forth greater attention to the prospect of abolition, it is time to think about what such ideas might mean for education. Remembering that abolition is not just about what we tear down, but about what new systems we build, it is time for a radical revisioning of education – for the sake of all students, but particularly those at the sharp end of structural harms.

Dr Remi Joseph-Salisbury is Presidential Fellow in Ethnicity and Inequalities at the University of Manchester. He authored the report Race and Racism in English Secondary Schools, and has recently co-authored, with Laura Connelly, the book Anti-Racist Scholar-Activism, published by Manchester University Press.

This article is the fourth in our series of reflections on 'everyday geographies', building up to the 2022 annual conference of the Geographical Association on this theme. You can read the first, by Gavin Brown on the Non-Stop Picket of the South African Embassy, here. The second, by Luke de Noronha on everyday racism and the violence of borders, is here. The third, by Lola Olufemi on 'everyday atrocity' can be read here.

The image at the head of this article is from an illustration by India Joseph, and is used here with thanks.