Teachers and support staff in the National Education Union (NEU) are balloting for strike action after 86% of teachers and 76% of support staff backed strike action against the government’s derisory unfunded, below-inflation pay offer in a preliminary electronic ballot. The NASUWT, another large teachers union, and even the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) are also balloting members - the latter for the first time in its history. In November, EIS began the first strike in Scottish schools for 40 years, and in England NEU Sixth Form college members struck in December after an 88.5% vote for action. Meanwhile the UCU, which represents university, Further Education, adult education and prison educators, has already won its own ballot for strike action, recently holding three days of solid and inspiring strike action at universities across the country.

As Sol Gamsu recently wrote, this could be “a historic moment for the education sector as a whole”, because from January it may be that education unions will be able to stage “coordinated action that brings education workers together across schools, colleges, universities and prison education”. In Gamsu’s words, education workers may find themselves in a position to “shut down the education factory”.

Nevertheless, we cannot take for granted the inevitability of a YES vote for strike action. Winning strike action first requires us to win the ballot, and that means both getting a majority to vote YES but, just as importantly, getting enough workers to vote to ensure we pass the government’s anti-strike thresholds and achieve at least a 50% turnout. Here, we lay out some of the reasons why we are calling for education workers to vote YES to strike action, and we hope that any colleagues who are yet to post their ballots will do so as soon as possible. And once you’ve voted, remember: this is just a first step in organising to win a better education sector.

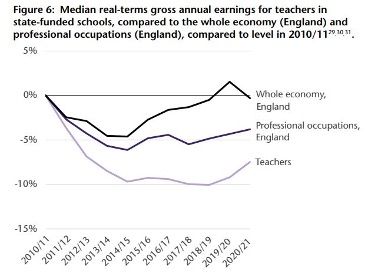

In schools, the immediate issue underlying strike ballots is a historic decline in real terms pay. According to the NEU, the value of a teacher’s salary has seen a real terms cut of 20% since 2010. As the Guardian recently reported, essential support staff in schools are leaving in ever larger numbers for higher pay in workplaces such as supermarkets. The graph below appeared in the independent School Teacher Review Body (STRB) report for 2022, which you can read in full here, showing changes in median teacher pay in comparison to pay in the whole economy and pay in other ‘professional occupations’:

The STRB commented that “Our analysis of real-term pay changes over time suggests that the competitiveness of teachers’ earnings compared to the whole economy, and to professional occupations, was lower in 2020/21 compared to 2010/11.”

As a result of falling real terms pay and excessive workloads, there has been a significant increase in staff leaving the profession, creating a recruitment and retention crisis that is severely afflicting schools. As the TES reported recently, geography has been particularly badly hit: at the end of the first half term this year, geography teacher vacancies were two thirds higher than at the equivalent point in 2019, pre-pandemic.

Across the education sector, grievances are legion. All education workers have seen their pensions eroded in recent years; in universities and Further Education colleges, precarious work conditions have been extended, with so-called ‘fire and rehire’ even being used at some FE colleges and mass redundancies proposed at universities; gendered and racialised pay gaps persist.

We know education is far from perfect. In 2020 research found that 46% of schools had no teachers from BAME backgrounds; Feyisa Demie has shown that school exclusions have increased, and continue to disproportionately impact on Black and SEND students; Ian Cushing and Julia Snell have shown how school literacy policies around ‘word gaps’ frame the language of BAME and working class students through deficit narratives that position the teacher as ‘saviour’, supported by a raciolinguistic surveillance and disciplinary apparatus that courses through the work of the school’s inspectorate, Ofsted; Christy Kulz has shown how the academisation of our school system has tightened the grip of marketisation and neoliberalism, at the same time as it has negatively impacted on the subjectivities of staff and students; and Christine Winter has shown how GCSE specifications and assessment materials encode ‘whiteness’ as a global norm and encourage students to think of Euro-American societies as superior to and more ‘developed’ than other regions of the world.

Nevertheless, education workers can, and do, resist these tendencies. Nor is this resistance confined to the UK. The last decade has witnessed inspiring struggles by education workers in contexts as different as Democratic Republic of Congo, Mexico, USA (where a handbook for teacher activism was produced), Cameroon and Iran, amongst other locations. Teacher struggles are truly global in scale.

This is the context within which UK education worker unions ballot for strike action. We recognise and acknowledge the pull of responsibility and care that teacher’s feel towards their students: we feel it too. But it is precisely this pull that should motivate us to vote YES to strike action in the current ballots, whatever union we are in (and to join a union and vote yes if we’re not yet in one). We cannot repeat it often enough: education staff working conditions are student learning conditions; the degradation of these working conditions degrades the quality of education. The fight for pay and conditions in education unites education workers across sectors with students and their families in the struggle for a better, more just, education for all.

Trade unions can be imperfect vehicles, as we noted when offering support and solidarity to the UCU previously. Nevertheless, recent struggles have had a transformative impact on education unions. Referring to the NEU, Jane Hardy in her book Nothing to Lose but our Chains, states that in recent years “30 per cent of new recruits to the NEU were teaching assistants”, that the percentage of NEU reps under the age of 40 rocketed from 31% to 50% by summer 2020, while the number of Black reps more than doubled from 3% to 7%. Women now make up 73% of NEU reps.

Within the education sector some of us are worried about the economic burden of striking. We will not allow this to divide our movement and will work hard to build solidarity. While we firmly believe that education workers cannot afford not to strike, we nevertheless urge national education unions to think hard about how to provide solidarity funding to support workers already in poverty on the picket lines. We urge local union groups to establish solidarity strike funds and mutual aid groups to provide care and support for vulnerable workers on or away from the picket lines. To workers questioning whether they can afford to strike or not we say: we hear you, we will do what we can to support you and to urge others to do so as well, and we hope that we can organise with you in care and solidarity so that we can strike together, win together, and fight the social production of vulnerability together.

Hardy argues that “far from being privileged workers hermetically sealed in the ivory towers of academia”, education workers have “been proletarianised by the neoliberalism of education.” What she means by this is that economic and political changes in recent years have worsened the pay and working conditions of education workers to such an extent that their own economic status has been moving backwards.

The current ballots offer an opportunity to organise within our communities to defend education, to argue for better funding for schools and other educational institutions, to oppose marketisation and to make clear the degree of exploitation that is occurring in educational workplaces. But doing this will require more than merely putting a cross in a box on our ballot papers, important as that is. It will require an immense effort of public pedagogy and popular political education, as we talk with our colleagues, students, and people across our communities about the dysfunctions at the heart of our education system and forge links and solidarities between teachers and support staff in educational institutions and people working and struggling in other sectors. Transformative change doesn’t happen just through industrial action: it requires us to organise democratically, to build solidarities openly, to make our case patiently, and to show an ethic of care towards others struggling in the face of our increasingly unequal society at the same time as we demonstrate a steely determination to win. It used to be a commonly heard slogan of the worker’s movement that we must educate, agitate, organise. Now is the time to do just that. So, vote now and vote YES, but don’t stop there.